|

Movies

I've Seen Lately

by Matt Silcock

John

Carpenter's Ghosts of Mars (John Carpenter, 2001)

Wacky movie in which John Carpenter borrows major elements

from several of his own movies (Assault on Precinct

13, The Thing, The Fog), slaps 'em all

onto Mars, and throws in a bunch of judo battles (oh

yeah, Big Trouble in Little China!) between

the good guys (a combination of sexy babes and blaxploitation

characters) and the bad guys (hordes of murderous

'indigenous peoples' who have a fashion sense somewhere

between the Texas Chainsaw Massacre family

and Marilyn Manson). With gratuitous battle scenes and

its 'weird desert outpost' setting, Ghosts

threatens to be another From Dusk 'Til Dawn,

but, for all his gleeful B-movie aesthetics, Carpenter

has more control than that. (There's also a subtext

considering the rights of colonists vs. the colonized....and

it's difficult to say which side the movie's on.)

Kwik

Stop (Michael Gilio, 2001) In the opening scene,

writer/director/lead actor Michael Gilio swaggers into

a convenience store, shoplifts, and swaggers out again.

He sports a pompadour, sideburns, and a leather jacket,

like some young Travolta/Liotta hybrid. A cute girl

in the parking lot calls him on his theft. He doesn’t

give out too much information about himself and may

in fact be up to more criminal things than shoplifting.

She bums a ride. Perfect hipster noir fodder, but the

movie simply refuses to take any generic turns, ending

up somewhere much closer to John Cassavetes than to

Doug Liman. As Didi, the girl in the parking lot, lead

actress Lara Phillips sees to that. Her performance

is goofy, sweet, and odd, and much like Gena Rowlands

did during the Cassavetes heyday, she constantly keeps

the movie on its toes. Gilio comes off as more of a

straight man, but within minutes they’re romancing,

exchanging lines like, Him: “You’re weird.”

Her: “You’re intense.” “Really?

Is that a good thing?” “It’s as good

as being weird.” Their road trip may not get very

far geographically, but it gets to plenty of places

emotionally, involving two more characters wonderfully

played by Rich Komenich and Karin Anglin. As a kooky

love story, it's better than Minnie and Moskowitz,

and as an independent movie (as of this writing, still

without a distributor), it's as good as anything I've

seen in years.

Bully

(Larry Clark, 2001) In which Larry Clark tackles

the same obsessions he did in Kids -- the beauty

and horror of ill-advised teenage lust -- and this time

gets it right. Kids certainly dove into its

topic, but the storyline and much of the acting was

just too contrived to allow me to forgive Clark his

signature mix of honesty and dishonesty. Now Clark has

some experience under his belt, and most importantly,

he's telling a true crime story (real names be proof),

so that all contrivances are the characters' own. The

dishonesty is still there -- just ask lead actress Bijou

Phillips, who Clark clearly has a leering interest in

-- but the honesty is more effective than ever. One

scene where two characters at a strip-mall play a violent

video game while stoned on LSD is a hilarious and harsh

depiction, better realism than anything in Kids.

The true story in question is that of a brutal murder

by suburban middle-class Florida teenagers. There were

7 accused and 1 victim in the Bobby Kent case, and in

this film version every performance is heroic: Brad

Renfro, who co-produced, Nick Stahl, who I didn't know

about before this (having not seen In The Bedroom),

Rachel Miner, in the Lady Macbeth role, Bijou Phillips,

in an amazing vision of true-life jailbait, Michael

Pitt and Daniel Franzese, who play the aforementioned

videogame scene, Kelli Garner, in an amazing vision

of true-life teenage death-glam, and Leo Fitzpatrick,

who appears in the last third of the movie as "The

Hitman," and shows that he has notably matured

as an actor since his infamous lead role in Kids.

Fando

Y Lis (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1968) Now I can

see why El Topo was such a slow, enervated,

and symbolically vapid film; because its auteur, the

almost tediously visionary film legend Alejandro Jodorowsky,

had already made something of a masterpiece two years

earlier, with Fando Y Lis, his very first feature-length

film. In a Jodorowsky interview/filmography published

in Forced Exposure magazine in 1991, Fando Y Lis

was declared 'a lost film’, but it has recently

been issued in a fine DVD version that also comes with

a decent documentary. Fando Y Lis, like Jodorowsky’s

post-Topo return-to-form The Holy Mountain,

is more or less a riff on one filmic event: Bunuel &

Dali's Un Chien Andalou and its chain of inspired

theater-of-cruelty non-sequitirs. Jodorowsky's version

is no less audaciously crafted, but there was a reason

that An Andalusian Dog was only 14 minutes

long -- stretched out to 90 or 120 minutes the Andalusian

approach becomes numbing, which has always been a thorn

in Jodorowsky's side. Another thing that’s always

bothered me about Jodorowsky is that he seems to take

his Artaud a little too literally. Here, these cruel

tendencies culminate when Fando drags the crippled Lis

down a rugged mountain path for a good 100 feet or so.

In another scene, Fando y Lis meet a pair of guys who,

in an uninterrupted take, use a syringe to draw blood

from Lis, empty it into a wine glass, and drink it down.

As for the included documentary, it could be better.

You get a lot of Jodorowsky hanging out in his study,

saying shit like, “I consider myself neither a

mystic nor an artist. I am someone who is playing games.”

(Got that right!) “All this Chinese, Japanese,

and Tibetan stuff goes directly to my balls. Illumination

doesn’t exist.” (You tell ‘em, Joddo!)

However, making all this sort of stuff worthwhile is

about 30 seconds of shocking footage of Jodorowsky’s

pre-film career theater troupe, which he called Panique.

If the mime sequence in El Topo and all the

amazing sets in The Holy Mountain didn’t

tell you, Jod’s real talent is the theater, and

why someone could put 30 seconds of this amazing footage

into a mundane documentary instead of just releasing

the whole damn thing as a feature film of its own is

beyond me. But either way, this is DEFINITELY a must-have

DVD for Jodorowsky aficionados.

Our

Lady of the Assassins (Barbet Schroeder, 2000)

I've always kept up with the films of Barbet Schroeder,

especially when he's not totally sucking Hollywood teat.

For this, his latest, he certainly isn't; in fact, it's

not even a film, it's a rather cheap looking video.

I kept getting PBS Masterpiece Theater vibes from the

way Assassins looks, which is strange considering

its violence and sexual content. In this film a rather

melancholy and apparently successful middle-aged writer

named Fernando (played by Germàn Jaramillo, who

gets the combination of bon vivant and misanthrope just

right), returns to his hometown of Medellin, Colombia

after years spent elsewhere. Upon arrival, he meets

an angelic teenage boy named Alexis (played by the frankly

luminous Anderson Ballesteros) who happens to be a cold-blooded

gangland hit-man. Fernando tells him, without further

explanation, that he has come back to Medellin to die,

and they make love. They move in together and spend

their days wandering the gun-ravaged streets. Fernando

philosophizes and complains, but Alexis takes care of

things in a much more conclusive manner. If you're ready,

the result is kind of stunning, like some new cross-cultural

city version of Badlands, a meditation on where

misanthropy becomes violence, and a slow nightmare vision

of how gangs and drugs and guns and poverty are taking

over urban space.

Terminal

U.S.A. (Jon Moritsugu, 1993) I've heard of

and approved of Moritsugu for years, all without having

ever seen anything by him. I finally caught up with

this 55-minute short made for a public television series

on the American family (!). For this production, he

found his usual budget of $10,000 skyrocketing to $365,000.

The result is a fabulous looking underground movie.

Although Moritsugu's anarchic aesthetic easily overpowers

any 'bourgeois' production values, the lurid soap opera

color scheme is stunning, resulting in a 1993 film that

looks like it could have just as easily been made in

1953, 1963, or 1973. As for characters and storyline,

it really is what I expected: the tried-and-true post-punk

pervo-suburban L.A.-deathride dysfunctional glam-rock

family schtick, a whole heaping of Waters with a pint

of Gregg Araki stirred in. One young brother is a spaced-out

drug pusher menaced by the same ultra-violent thugs

that the other young brother, a bookworm math-geek (both

are played by Moritsugu), hopes can bring his gay skinhead

masturbation fantasies to life. Their sister is horny

and easy and is about to manipulated into a career as

a sex slave porno actress. Dad is goofy, impotent, and

wants to take his family to some sort of promised land

(by killing them). Father-in-law is a vegetable, and

mom, hooked on his pain medication, is an IV drug user.

(Had to be IV drug use in there somewhere, right?) All

that, I expected; what I didn't expect was it to be

as well-done and outright hilarious as it is. The style

of anti-acting that the cast takes and runs with is

truly funny; some of the line readings in here have

to be heard to be believed.

Rosemary's

Baby (Roman Polanski, 1969) One of the reasons

I married my wife, besides just loving her and all that,

was that she always surprised me with her insights on

books she’d read and movies she’d seen.

No matter how much I had gotten out of the same book

or movie, she had some simple statement that made me

see it in a whole new light. Recently she really knocked

me for a loop with a comment about Rosemary’s

Baby. A horror movie about pregnancy, I considered it

one of the most uncomfortable movies I’d ever

seen – talk about hitting you where you live.

We watched it together on video about 4 or 5 years ago

and haven’t seen it since, but just a week or

so ago Caryn, after thinking a bit, asked out of the

blue, “What happens at the end of Rosemary’s

Baby?” “All the satanists are gathered around

celebrating the son of satan being born,” I answered.

“Do we see the baby?” “No, we never

see the baby. There’s a camera from the point

of view of the baby, like from inside the carriage,

and she just looks down at it and smiles and reaches

out to it or whatever, showing that she’s part

of the clan.” “Well, how do we know that

they’re all satanists?” “Whuh???”

“Maybe they’re not really satanists, and

most of the movie is a fantasy sequence, like a metaphor

for her paranoia and pregnancy weirdness, and then at

the end she smiles because she realizes everything is

okay and she’s had a normal child and all the

people who were scaring her really are just her friends

after all.” I mean, holy shit…she could

be right!

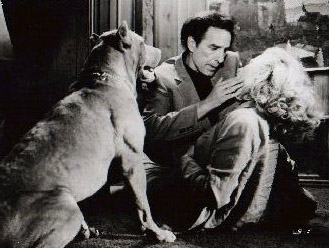

Love

Streams (John Cassavetes, 1984) What a fucking

film. Somehow way overlong without having a single superfluous

scene, this is Cassavetes at his most aggravating, achieving

one of his grandest overall gestures: simply, a man

saying goodbye to his loved ones and the rest of the

world from inside his house. He’s holed himself

up for good, physically and spiritually, and that's

really all this epic is about. The house theory isn’t

mine, I just read it a couple weeks ago at sensesofcinema.com,

in an essay by Adrian Martin called "John Cassavetes:

Inventor of Forms," which says, "The house

in Love Streams....is all at once a home, a

club, a menagerie, the set for Prospero's imaginings,

and Noah's Ark during the great flood. The house is

the film's generative space: the entire course of the

story follows the uncertain lineaments of this architectural,

habitable marvel into hallucination, reverie, madness."

I think Love Streams is Cassavetes' best film.

Until I saw this, my pick was Opening Night.

The canonical choice would be probably be Faces....Okay,

call Love Streams the third best Cassavetes

film. With a bullet.

Atanarjuat,

The Fast Runner (Zacharias Kunuk, 2001) Nice

to have a three-hour long film about Native American

(Canadian, to be exact) culture that doesn't have a

Kevin Costner 'white guide' figure to lead the viewer

through it. No, The Fast Runner puts you, not

Kevin Costner, squarely inside the igloo, sitting next

to these cold raw-meat eating peoples who've never seen

a white man and never will and you've gotta get used

to it. The experience is almost science fiction (those

huge landscape shots straight outta 2001 help)

except that everything, besides a pinch of folktale

magic here and there, seems irrefutably like fact. I

was thinking, "Yeah, this could be set in contemporary

times," until I read that it was set at "the

dawn of the first millenium." Oh well. When you

live inside the Arctic Circle, I guess descriptors like

'contemporary' don't matter so much. This film puts

you there.

Nude

On The Moon (Doris Wishman, 1964) They certainly

don't make 'em like this anymore. After seeing a couple

vintage Doris Wishman flicks, you might confuse Ed Wood

with Orson Welles. Two guys travel to the moon by putting

on construction coveralls and getting into the cab of

a semi truck. They shift a couple gears and flip a couple

of switches on the air conditioning. When they run out

of pseudo-astronaut things to do, Doris has 'em just

fall asleep, then shakes the camera to signify the 'landing.'

They wake up and go, "Well, we're here!" They

get out and it's all sunny and green and filled with

palm trees (not to mention plenty of oxygen) because

it's actually Florida. That this isn't what the moon

is really like isn't explained whatsoever, except by

one of the astronauts saying, "Wow, it sure is

nice here on the moon!" Jeez, I can't go on with

the review, because it's just too brilliantly audacious

for words. (Oh yeah, all this gloriously rushed exposition

takes place because Wishman is in a hurry to get to

the ticket-selling plot point: the moon is inhabited

by a bunch of nude women.)

Possession

(Andrzej Zurlawski, 1981) After going through

a difficult divorce, visually brilliant and thematically

stupid Polish director Andzrej Zulawksi pitched to some

filthy rich investor a movie about “a woman who

fucks with an octopus.” For some reason the investor

went for it, and the result was this repulsive and obscenely

over-budgeted movie, much worse than even the pitch

makes it sound. A young Sam Neill plays the least likably

estranged husband in history, and Isabelle Adjani plays

his severely troubled wife. She really does fuck with

an octopus, a tentacled Carlo “E.T.” Rambaldi-designed

symbol of some kind that she keeps hidden away in a

secret apartment. Oh yeah, it's also her child. Meanwhile,

at her other apartment, she and Neill thrash around

and scream in divorce fights that make the most histrionic

family moments in a Cassavetes film seem like the Steve

Martin remake of Father of the Bride. At every

turn, in between all the stunning tracking shots of

alienating post-modern interiors, Zurlawski gratuitously

puts his characters through ridiculous and ultra-violent

decisions and situations. For example, during one argument

in a kitchen, Adjani’s clearly lunatic character

frantically works away with a carving knife and a meat

grinder; what happens next isn’t exactly a surprise.

The acting in this movie is really obnoxious all around

– only notable for its decadent extremity. Somehow

Adjani won Best Actress awards at Cannes. They should’ve

just given it to Georgina Spelvin or Linda Lovelace.

Sure, there are images and sequences in here that are

unforgettable, but I’m sure witnessing a murder

or other shocking crime is unforgettable too, and if

a viewer gets his kicks from merely collecting extreme

images for his 21st-century mental rolodex, he probably

shouldn’t miss Possession. After it’s

over, Zulawski’s overblown vision of total marital

breakdown does have some staying power, but that is

no reason to sit through all 141 muddled minutes.

Eyes

Without A Face (Georges Franju, 1959) I can’t

imagine how downright creepy this must have been when

it came out, because it’s still very unsettling.

At first it seems possibly too low-key and slow-moving,

but then the unforgettable central image of a disfigured

young woman made to wear an eerie mask appears, and

a disturbing story starts to take shape around it. Almost

every moment that follows is a textbook of how to do

perverse horror with class and calmness, a lesson that

Hollywood simply can’t get right anymore. (BTW,

I think that Georges Sluizer drew heavily on this film

for his The Vanishing, right down to the character

of the calm, intelligent, and bearded psychopath doctor

that both movies share.)

Mulholland

Drive (David Lynch, 2001) I really don’t

feel like interpreting the uninterpretable right now.

I did enjoy the first hour and 45 minutes immensely,

with a classic noir storyline (it's an amnesia picture!)

given the most deadpan Lynchian treatment yet, but,

just as in Lost Highway, at some point everything

just changes. It’s like a bizarro-world mystery

story; there are plenty of clues, but each one somehow

leads the viewer further from the solution. I guess

it’s simple, really: a film about how Hollywood

kills naivete, but there's just so much to unpack. I

really dug it, though; the sumptious/clinical L.A. setting,

the hot lesbian love-making, and all the bizarrely Lynchian

walk-on characters like Michael Des Barres as Cowboy

Billy, Billy Ray Cyrus as the pool guy, somebody as

the hipster director, and of course somebody as the

monster-man who lives behind the Denny's. (Seemed to

be a continuation of the "Man in the Planet"

character from Eraserhead, but I'm not really

a fully accredited student of Lynch or anything.)

L'Eau

Froide/Cold Water (Olivier Assayas, 1994) Just

a few weeks ago Newsweek had a cover story

on depression among middle-class teenagers, but writer/director

Olivier Assayas was already on the case with this devastating

fiction film. It was set in 1972, and commissioned by

French Public Television in 1994 as part of a series

in which directors were asked to make a film set in

the years of their youth. It seems strange to even say

that this movie was made in 1994, because it feels so

much like 1972 and 1982 and 2002 that I really had no

idea when it was made. (That's what critics mean by

the adjective "timeless.") In some ways this

could be Assayas's tribute to Bresson's The Devil,

Probably, which he wrote an essay about during

his stint as a film critic. Certainly Gilles (Cyprien

Fouquet), the young male lead who steals, gives explosives

to little kids, fails in school, and yells at his father,

is as tragic of a character as Bresson's Charles. But

the main character is his girlfriend, Christine, played

tragically and luminously by Virginie Ledoyen. Much

has been said about this film's extended bonfire party

sequence, and it is something, but not in any 'teen

party' sense you may be accustomed to from American

films. Mostly, it made me feel like crying, and after

the end credits rolled and the house lights came up,

I felt as sad as I've ever felt upon finishing a film.

(At the same time, no other film I've seen captures

the fleeting beauty of great rock music like Cold

Water. Dylan's "Knockin' on Heaven's Door"

sets a devastating tone during the party sequence, and

there's a thrilling sequence when Gilles and his younger

brother surreptitiously tune in Roxy Music's "Virginia

Plain" on a transistor radio in their kitchen.)

CQ

(Roman Coppola, 2001) Couldn't quite make it

through this on DVD. It's supposed to be set in 1968

or 1969, but Austin Powers and Barbarella homages alone

do not a period piece make. Maybe it's because Jeremy

Davies plays exactly the kind of dishevelled, affectedly

soft-spoken aspiring filmmaker I seem to meet once a

week here in 2002. Oh, I guess it is 1969, though, because

he wears a suit everywhere. Jason Schwartzmann is supposed

to be intentionally annoying as a hot-shot wanna-be

film director, but he's also unintentionally annoying.

Just like this movie. As far as Coppola family nepotism

goes, The Virgin Suicides was a lot better.

*Corpus

Callosum (Michael Snow, 2001) I’ve never

seen the famous Wavelength, or anything else

by Snow, until this. It was shot on digital video, and

lasts 90 minutes with a vertical (as opposed to the

usual horizontal) storyline, features a lot of trickery

and goofiness, and was called “the best feature

film I’ve seen so far this year” by Jonathan

Rosenbaum. Well, Johnny, I love your work, but I don’t

know if I’d go that far. It is a pretty exhausting,

disorienting experience, although a lot of that has

to do with the rather harsh noise on the soundtrack,

which sometimes gets so loud that several people in

the audience I saw it with were holding their ears.

There is a lot of dry wit and imaginative stuff going

on, some of which I won’t soon forget, and it

all has something to say about the way we pass the day

in the so-called 'cubical culture,' without forgetting

the cubicals we have at home. Technology and artifice

in general are also heavily commented on, at first obliquely,

but with a lot of staying power. I'm still thinking

about this one almost every day -- maybe Rosenbaum was

right.

Hugo

Pool (Robert Downey, 1997) This is my first

Downey film; I haven't even seen Putney Swope.

I'm sure some will say that I shouldn't have started

with this one, but I ended up really liking it a lot.

Sure, it's 'flawed' -- in fact, it's deeply disturbed,

and, at several moments during the elliptical narrative,

characters seem to be stranded onscreen without dialogue,

unable to ad lib. But I ended up liking almost every

single member of the big, weird cast of characters.

Maybe I was distracted by her beauty, but I thought

Alyssa Milano's performance was excellent in the lead

role, as a young woman named Hugo Dugay who runs her

family pool-cleaning business. Malcom McDowell, adopting

a not-all-there New York gangster accent, plays her

ex-junkie father, and Cathy Moriarty plays her compulsive

gambling mother, only about two steps from full-on floozy-hood.

She has a love interest, Patrick Dempsey, looking very

handsome as a client with Lou Gehrig's disease who speaks

Stephen Hawking-style through a laptop computer. His

performance is great too, radiating calmness and inner

serenity. And Sean Penn, as a character who I believe

to be a figment of McDowell's character's imagination,

gives my favorite performance of his since Fast

Times At Ridgemont High!

Blow

(Ted Demme, 2001) The original Yo! MTV Raps

is the late Ted Demme's greatest contribution to the

culture. (Possibly MTV's too.) As for his movies, this

may be his magnum opus, but it's still Scorcese Lite.

I knew it was a true story, but during the first few

scenes, set in Manhattan Beach, California, I started

to wonder....when did this story take place? 1990? 1981?

1978? When the next title card read "1969" I was a bit

taken aback. Johnny Depp is always good, and I mean

ALWAYS. Here, he even shows an ability to act well while

wearing an increasingly goofy series of long-hair wigs.

(Don't miss the brief appearance of a handlebar moustache

during a montage with the Allman Brothers on the soundtrack.)

Dubious costuming aside, like any post-Goodfellas

movie about the life of a drug dealer, Blow spends

most of its running time showing how profitable, easy,

and glamorous of a business it is, before tacking on

the requisite ten-minute coda about why you should avoid

these vast riches and pleasures at all costs. Actually,

Blow's ten-minute coda was surprisingly moving.

And props go to Max Perlich, in a smaller part.

Bowling

For Columbine (Michael Moore, 2002) I've never

even really been a Michael Moore fan, but I know a cry

from the heart and soul when I see it and with this

film essay Moore has done it. The tone -- rambling,

usually entertaining, sometimes hilarious -- reminds

me of Roger & Me, but this is a movie about

gun violence, which means that it's also sometimes heartbreaking.

Moore's discursiveness and digressiveness reminds me

of another movie I just saw, Agnes Varda's The Gleaners

and I, which I say just to point out that this

is not some goofy 'let's take on those evil corporations'

propaganda piece. This movie will make you sad, and,

hopefully, pretty goddamn angry; after one clip of a

smug and conniving George W. Bush I actually said "fuck

you" out loud to the screen. Usually when filmmakers

try to provoke me, I end up being mad at the filmmaker,

but Moore does it correctly, so that I end up being

mad at someone else. In this case, it's our thieving,

conniving president of course, but also our entire fucking

mass media. He asks a simple question: Why does America

have 11,000 gun deaths a year while the second highest

nation in the world is under 400? He rules out the usual

liberal-arts apologies (Moore is a card-carrying member

of the NRA); one, that we have more guns than any other

country (Canada has more per capita), and two, that

violence is part of our national history (Russia and

Germany have both killed more people). Amazingly, Moore

(with a lot of help from Marilyn Manson and South

Park co-creator Matt Stone, who both offer some

of the most reasonable cultural critique I've heard

in a while), finds a new explanation: that we live in

a culture of fear, created, simply, by American mass

media, in which 'the national news' is in reality 'the

national warnings,' whether of the West Nile Virus or

of Weapons of Mass Destruction (all those except our

own), or, for god's sake, "Africanized" killer

bees. (The section where he demonstrates how rude our

mass media is to the African-American is infuriating

and thank god he did it.)

BLASTITUDE

#14

next

page: why not some book reviews?

|